DSO of the Month

Messier 81 and Messier 82

AKA: Bode’s Galaxy (M81) and Bode’s Galaxies (both); Cigar Galaxy (M82);

NGC 3031 (M81) and NGC 3034 (M82)

Position: 9 hr 55.5 min 69 deg 03 min 55 sec (M81)

Position: 9 hr 55.9 min 69 deg 40 min 47 sec (M81)

Due south at 22:23 (GMT) on 15 March

M82 on the left and M81 on the right. Image by Les Brand

Usually I would say that galaxies are not visible from most of Havering, at least not clearly. There are a few exceptions, the most obvious being the Andromeda Galaxy, M31 (to be covered in a future DSO of the Month). Another two exceptions are M81 and M82, which are conveniently circumpolar and close together. They can be seen in a small telescope in suburban skies without any great difficulty. I remember when the supernova in M82 was announced in January 2014 (SN2014J); I was able to find M82 and see the supernova itself. M82 is fairly easy to see, being long and thin although only magnitude 8.4. M81 as a face-on spiral is somewhat more difficult to make out, despite being magnitude 7 and about half the size of the full moon. But in contrast to say M33 or M101, they are straight-forward to find and view. To find them draw a line across the bowl of the Plough between Gamma Ursae Majoris (Phad) and Alpha Ursae Majoris (Dubhe) and then follow the line north-westwards as far again (it will bisect the meridian of Polaris, but that will probably not be easy to spot). I find a filter (a contrast filter or a light pollution filter) offers no advantage here and in fact dims the galaxies significantly. The two galaxies were discovered by the German astronomer Johann Elert Bode (famous for his planetary “law”) on 31 December 1774. Five years later they were rediscovered by Pierre Méchain and then included by Charles Messier in his catalogue.

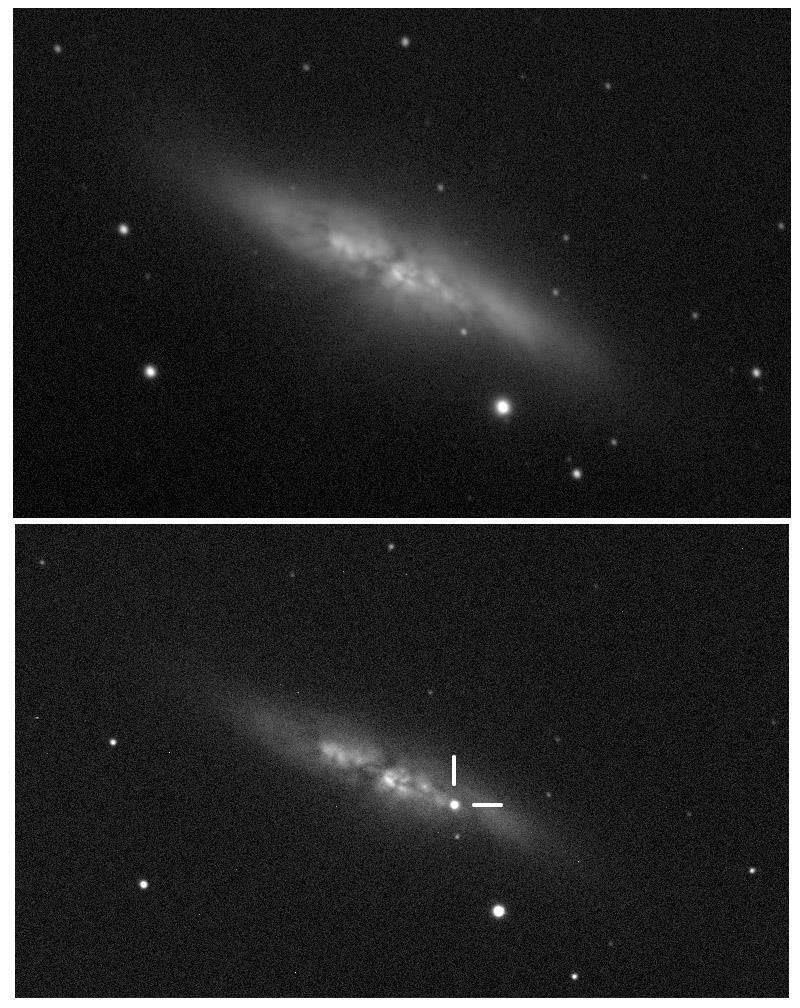

M81 is the largest member of the M81 group and there is a gravitational interaction between M81, M82 and NGC 3077. At 11.7 million light years away the galaxies are a relatively close neighbour of our Milky Way although much further away than M31. M81 is a fairly standard spiral galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its centre, but M82 is more interesting. For many years (and for obvious reasons) it was considered to be an irregular galaxy, but recent infrared observations have detected spiral arms showing that it is actually a spiral galaxy seen edge-on. Even in a small telescope, M82 looks fairly traumatised and this is a result of its gravitational interaction with M81. Such interactions encourage star formation (as in the case of our galaxy’s Magellanic Clouds) and M82 is a major starburst galaxy. There were three starburst episodes several million years ago which is almost yesterday in stellar terms. Such starbursts produce massive stars which then go supernova fairly quickly (a few million years or so), hence SN2014J. The red filaments around the centre of the galaxy which are often obvious in photographic images (as in the image above) are not visible in the telescope. The telescopic view only shows a dark lane in the middle (the black and white image below corresponds fairly well to the telescopic view in a small telescope)

The Type Ia supernova (SN2014J) in M82. Credit: UCL/University of London Observatory/Steve Fossey/Ben Cooke/Guy Pollack/Matthew Wilde/Thomas Wright - UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

ARCHIVE