DSO of the Month :

Messier 31

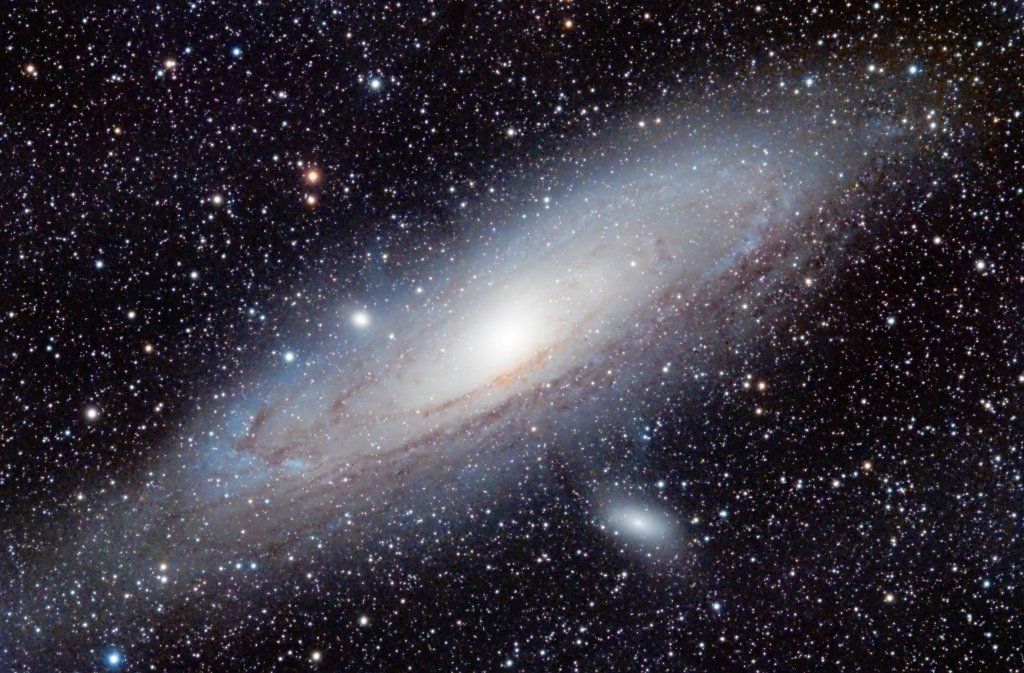

AKA: Andromeda Galaxy, NGC 224

Position: 00 hrs 42 min 44 sec + 41 degrees 16 min 09 sec

Due south at 21:04 (GMT) on 15 November 2021

Messier 31

Image: Les Brand, HAS member. Used with permission.

Sadly galaxies are not easy to observe in light-polluted areas and even when they can be seen, the result is often disappointing, so I rarely make them a DSO of the Month. However there is one major exception to this rule, namely the Andromeda Galaxy. It cannot be seen with the naked eye in Havering but I have seen it as a silver glimmer in a moderately light-polluted area (in northern Belgium as it happens). It can easily be seen through binoculars and it is a splendid sight even in small telescopes. In terms of being seen, the Andromeda Galaxy has three advantages: it is relatively nearby, it is large and it is tilted so we do not see it face on (for more on this see DSO of the Month for November 2019).

Clearly such a bright object should have been seen by the ancient astronomers and it is an indication of their fixation with stars and planets that the first observer to record it was the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi around 964. He described as a nebulous smear (compare my “silver glimmer”) and it became known as the little cloud (i.e. nubecula, hence nebula). It was first seen in a telescope by the German astronomer Simon Marius in 1612, and Charles Messier added it to his catalogue in 1764. The French mathematician Pierre Louis Maupertuis wondered as early as 1745 if it was an island universe, but nearly all observers (including William Herschel) up to the end of the nineteenth century thought it was a star cluster in the Milky Way Galaxy. Then in the early twentieth century, two facts began to disturb the accepted view. Vesto Slipher measured it to be the fastest rotating object in the Milky Way and Curtis Heber noted that the novae in the Andromeda Nebula were far fainter than other novae in the Milky Way; indeed a supernova observed in the Andromeda Nebula in 1885 was assumed to be a dim nova. Finally the debate about the location of the Andromeda Nebula was settled by Edwin Hubble in 1925 when he identified Cepheid variables in M31. As the absolute magnitude of a Cepheid variable can be calcuated (see Double Star of the Month for October 2019), it was easy to show that M31 must lie well outside our own galaxy. The hitherto Andromeda Nebula and its fuzzy relatives were indeed galaxies in their own right. It is now known to be 2.5 million light years away from us. It is disputed whether the Andromeda Galaxy is more massive than our own galaxy, most likely they are about the same mass (800 billion to a trillion solar masses). M31 is the largest of the galaxies near us in terms of its diameter, which is 220,000 light years; more than twice the size of our galaxy.

To find the Andromeda Galaxy in the sky, look for a line of bright 2nd magnitude stars high in the southern sky at this time of year, namely Scheat (Beta Pegasi), Alpheratz (Alpha Andromedae) – these two stars are the top half of the Square of Pegasus – Mirach (Beta Andromedae) and Almaak (Gamma Andromedae). Now go back to Mirach and head upwards to the fairly dim (mag. 3.9) Mu Andromedae and then up as far again to even dimmer (mag. 4.5) Nu Andromedae, and just to the right of Nu Andromedae is M31. Actually if you are using binoculars or a finderscope (or lucky you, you are in a dark area), the last two steps are hardly needed; the Andromeda Galaxy should be pretty obvious above Mirach. Enjoy the sight!

ARCHIVE